If the COVID-19 pandemic has given us any silver lining, it's that it has greatly influenced the way our medical society approaches studies and clinical trials. While the worldwide crisis has undoubtedly caused devastation on levels most of us haven't experienced before, it has sparked a recognition of the importance of gender and ethnic diversity in medical research.

As a women's healthcare expert with 35 years of experience, it has long been a goal of mine to convince healthcare providers, researchers, government health organizations and other medical experts that research should always include women and ethnic minorities.

Now more than ever, while we navigate the COVID-19 crisis and continue to address other healthcare concerns (like diabetes and strokes), it's essential that women and minorities sign up to participate in clinical trials to help the medical community better understand these differences. Their participation helps boost medical knowledge of healthcare issues and any existing disparities to, in turn, develop more effective treatment and prevention options.

How do clinical trials work?

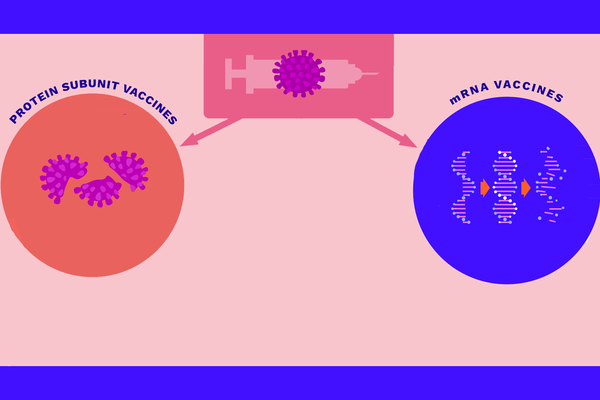

There are two main types of clinical trials: interventional and observational. Interventional clinical trials aim to manipulate participants' environments to modify a health process. Observational clinical trials, on the other hand, observe participants' behavior and how different lifestyles may affect a health process. Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, we have seen both types of studies being used to develop treatments and preventive measures.

Clinical trials are usually completed in a series of five phases before reaching FDA approval. Phases 0 and 1 begin with very small groups of people to determine safety and dosage of a drug that is being tested. Phase 2 then studies a larger group for a longer period of time and looks at efficacy and side effects. Phase 3 once again grows in size and duration, further monitoring efficacy and potential adverse reactions and comparing the new drug to an existing one. The final phase includes the largest pool of participants to rule out any lingering concerns.

A history of women in clinical trials

Statistically based clinical trials in America started to appear in the 19th century and gained popularity in the mid-20th century following World War II. However, for a very long time, clinical trials included only male participants. It wasn't until as recently as the women's rights movement of the 1960s and 1970s that policies were first introduced to encourage the inclusion of women in research.

In 1993, Congress finally wrote a policy into federal law that allowed both women and minorities to participate as subjects in clinical research. This was an official acknowledgement that men, women and minorities all differ in their healthcare needs. This year, we'll even see the first industrywide principles on clinical trial diversity go into effect in April.

These new principles, determined by the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, will aim to address four main areas. They'll strive to build trust and acknowledge historic mistrust of clinical trials within Black and brown communities; reduce barriers to clinical trial access; use real-world data to enhance information on diverse populations; and enhance information about diversity and inclusion in clinical trial participation.

While these principles are a huge step in the right direction, participation will ultimately rest with more women and minorities volunteering to be a part of these trials. By building trust like the principles outline, I can only hope that we will see many positive changes (and better treatments) emerge from clinical trials in the near future.

COVID-19’s impact on clinical trial participation

Since COVID-19 first began, we've gotten off to a good start in helping accomplish the goal of creating more diverse clinical trials. There was a huge push in 2020 for Black, Latinx and American Indian volunteers to join COVID-19 vaccine research. It was a critical element of developing an effective vaccine, since the virus disproportionately affects Black, Asian, Hispanic and other minority groups. Black individuals, for example, see 2.8 times more deaths from COVID-19 than white individuals.

Historically, minorities have made up smaller populations of many clinical trials compared to white subjects, and this trend continues today. Women are also regularly underrepresented, even in the most essential trials. For example, although cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death for women in the United States, killing over 300,000 women in 2019 alone, cardiovascular clinical trials are still made up of less than 50% women — a number that should be split evenly with male participants.

My goal is that, now that we've seen the changes in attitude brought about by COVID-19, we'll continue to diversify clinical trials across the healthcare spectrum to become more equal and representative in nature. Men, women, minorities and even pregnant women and children all deserve a chance to have their unique health needs accounted for in both research and available treatments. There is a greater urgency than ever to analyze these differences.

Although our main focus is presently COVID-19, it's important that we continue to research and study other concerns like hereditary cancers, pancreatic disease and more. The only way pharmaceutical companies and research institutions can discover new treatments is to conduct clinical trials focused on developing solutions for deadly diseases that affect us all and to encourage diverse participation in research.

By including all groups, we stand the chance of developing more personalized medicines and therapies that can alter the course of diseases for good. In order to find these answers to the many healthcare issues we deal with today, I encourage you to consider learning more about how you and your loved ones can participate in clinical trials. You can ask your doctor, search online or visit clinicaltrials.gov to locate a trial near you.

- We Need More Black Women in Clinical Trials ›

- Why Diversity in Clinical Trials Is Important - HealthyWomen ›

- Diversity in Cancer Clinical Trials - HealthyWomen ›

- Diversidad en los ensayos clínicos de cáncer - HealthyWomen ›

- Immunocompromised People and Covid-19 Clinical Trials - HealthyWomen ›

- HW Is a Convener on the COVID-19 Vaccine Education Project - HealthyWomen ›