As told to Alex Fulton

As people around the world wait eagerly for their turn to get vaccinated against COVID-19, I've been reflecting on my experience with a different, equally earth-shattering scientific breakthrough — the polio vaccine.

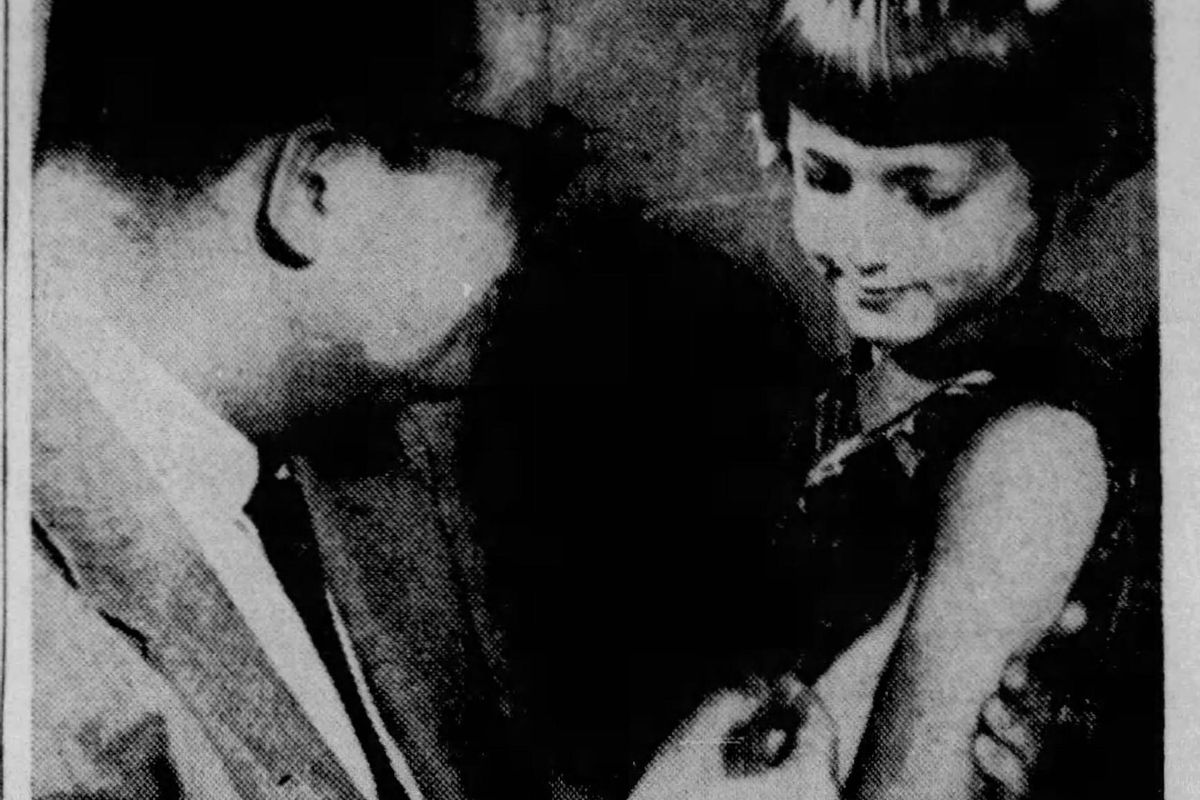

Starting in the spring of 1954, a group of children known as "Polio Pioneers" began to receive the polio vaccine invented by Jonas Salk. At the age of six, I was one of them as the first child in LaCrosse County, Wisconsin, to be inoculated with the Salk vaccine.

Polio is a highly contagious viral illness that can cause paralysis in a matter of hours and leads to death in 5% to 10% of those who are paralyzed.

The scariest part? Polio mainly affects children under the age of five. And in the 1950s it was spreading like wildfire.

Although I have many happy childhood memories, being a little kid during a polio epidemic isn't one of them. Much like with the COVID-19 pandemic today, we were forced to isolate in an attempt to slow the spread of a virus. The big difference is that it was children who were most at risk of becoming infected with polio.

Quarantines were imposed across the country, and travel was restricted. In the area where I grew up, the threat of polio was so serious that in 1945, the health department prohibited all gatherings outside of school for children under the age of 16. They only kept the schools open because they didn't have any other way to keep track of which kids were sick.

Summertime was the worst. Beaches, pools, movie theaters and basically any place we would normally get together to have fun were all closed. Instead of running around, playing outside with our friends, we were cooped up indoors.

At home, we watched our parents' foreheads crease with worry every time we sneezed. We saw the fear in their eyes as they talked in hushed voices about how quickly the disease was spreading and about how many children were dying.

Even in my tiny town with its one-room schoolhouse, none of us were safe from polio. I remember a sweet little boy who lived in our neighborhood getting it. He recovered but was left with a permanent limp.

When word of Salk's polio vaccine spread, the relief was palpable. People celebrated just like they did when the COVID-19 vaccine was announced — yet another parallel between then and now. It's remarkable to be reliving such a monumental moment.

I don't know exactly why I was chosen to be the first person in my county to get Salk's vaccine, but I can only guess that my parents jumped at the chance to make me a "Polio Pioneer." They were firm believers in science and had always been proactive about getting my siblings and me vaccinated on schedule.

I imagine they must have been at least a little bit worried. If the thought of getting a brand-new vaccine fills you with apprehension, imagine what it was like offering up your six-year-old daughter for one. But my parents never wavered, at least not in front of me.

There was no discussion, no listing of pros and cons. No amount of concern over possible side effects or other unknowns associated with a new vaccine could compare to the terrifying threat of polio.

Maybe because my parents didn't seem worried about me getting the polio vaccine, I wasn't, either. I don't remember feeling scared when I walked into the room where the doctor waited — along with a reporter from the local newspaper who was sent to cover the occasion. According to the article he wrote, I didn't even flinch when I got my shot.

I still have a clipping of that article. And when I see news reports showing early recipients of the COVID-19 vaccine, I feel a kinship with these people. They're pioneers, too.

I know we're not living in the 1950s anymore, and COVID-19 and polio aren't the same illness. But their vaccines have something very important in common — a reason to hope.

I understand why some people may feel anxious about getting the COVID-19 vaccine. It's normal to fear the unknown, and this vaccine is as new as Salk's polio vaccine was in 1954.

That's why I feel compelled to share my own vaccination story.

I want people who may be on the fence about getting the COVID-19 vaccine to consider my parents' situation. Along with the families of over 1.3 million American children who participated in Salk's polio vaccine trial, they took a chance on a new vaccine because they believed it would keep me safe, but also because they understood that it could benefit the whole world.

I want us to be as brave now as my parents were then. I want people to trust science the way my family did, so we can wipe out this virus the same way we wiped out polio.

I was first in line to get the polio shot, and I'll be getting my COVID-19 vaccine as soon as I can. I hope you will, too.

- Did You Get a Polio Vaccine as a Child? Here's How to Find Out. - HealthyWomen ›

- Common Diseases and Their Vaccines - HealthyWomen ›

- The Dark Days Before Vaccines - HealthyWomen ›