After bladder cancer treatment, a woman is often left struggling. She looks in the mirror at her new body, maybe with a urostomy bag attached, and worries that she’s no longer sexy and her sex life will never be the same.

But there is hope for her — and all bladder cancer patients. It is possible to have a healthy, satisfying sex life after bladder cancer treatment.

Stages and treatment

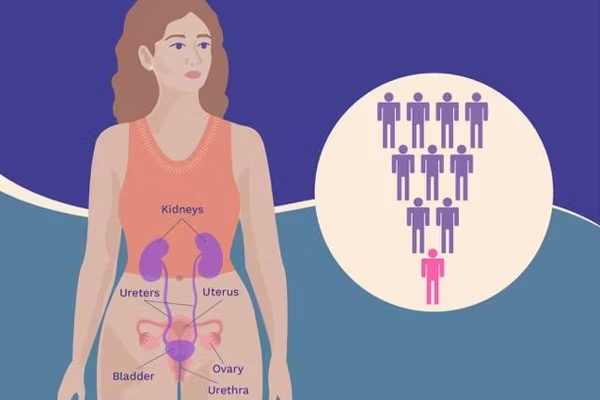

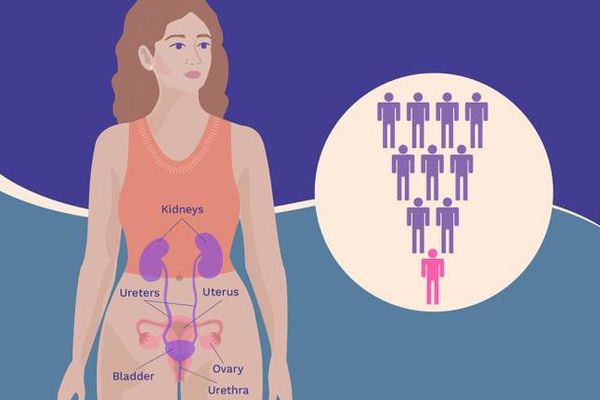

Non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) occurs in the lining of the bladder and is the most common stage of bladder cancer in the United States. The treatment of NMIBC often involves scraping the tumor from the bladder wall and, in some cases, inserting medicine directly into the bladder. In rare situations, the bladder may need to be removed in a cystectomy. “We may remove the patient's bladder if the type of the tumor is of an extremely aggressive subtype or if they fail the conservative approaches,” Armine Smith, M.D., a urologic oncologist at Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore, wrote in an email.

Later stage bladder cancer, muscle invasive bladder cancer (MIBC), occurs when the cancer has spread into the muscles of the bladder wall. The traditional treatment for MIBC is chemotherapy followed by a radical cystectomy, which is the removal of the bladder and the nearby organs, including the uterus, fallopian tubes, ovaries and part of the vagina. After surgery, doctors create a new way for urine to leave the body. This may result in a stoma — an opening in the abdomen. A patient may also have a urostomy bag — a pouch outside the body that collects urine.

A new body

With both NMIBC and MIBC, patients may experiences bodily changes that affect their sex lives. “Bladder treatments of any kind … may affect urinary function and cause pelvic pain, which in turn can affect the sex life of a woman,” wrote Smith. “These changes can be temporary or permanent.” Patients may also experience side effects like vaginal dryness, lowered sex drive and fear of contaminating partners with medicines, and having a radical cystectcomy will bring about menopause if the woman is not already postmenopausal.

“The removal of the sexual organs can cause menopausal symptoms because you're removing the organs that produce hormones that help with a lot of sexual functions, such as lubrication,” said Andrea Apolo, M.D., a medical oncologist at the National Cancer Institute in Bethesda, Maryland. Women can fight this lack of natural lubrication with store-bought lubricants or vaginal hormones when appropriate.

“After surgery like this, we want to get the vagina feeling happy again. Vaginal hormones can help the vagina feel more supple and stretchy,” said Heather Bartos, M.D., an OB-GYN and member of HealthyWomen’s Women’s Health Advisory Council.

A radical cystectomy may also shorten the vagina, which can cause painful intercourse and penetration. Solutions include vaginal dilators — plastic, cone-shaped objects used to stretch the vagina — and vaginal reconstruction, a surgical procedure that lengthens the vagina.

Pelvic exercises, like kegels, can also be helpful after a cystectomy. Working with a physical therapist may help as well. “A pelvic floor physical therapist can help release muscle tension down there and release any kind of scar tissue,” Bartos said.

Nerve damage can also occur during a cystectomy. Nerve bundles inside the vagina can be damaged, and if the end of the urethra is removed, the clitoris may lose sensitivity. Patients should talk to their doctors before surgery about possibly sparing these areas.

Emotional impact

“Any time there’s cancer in the pelvic organs and a woman needs to have all of those organs removed, there’s a lot of emotional trauma,” said Bartos. Apolo explained it as patients needing to adjust to what she calls “a new state of being.” According to Smith, women face many issues when they are diagnosed with bladder cancer. These issues can include depression and anxiety, which can translate into decreased sexual desire or satisfaction. Some of these issues may be caused by the emotional toll of the diagnosis or the treatment, and others may be caused by the physical changes resulting from the treatment.

Addressing the emotional aftermath of bladder cancer, possibly with a mental health professional, is important for sexual health. “Talking to a therapist, in either individual [or] couples therapy or both, can really help get those emotions out,” Bartos said.

Many women also experience a lack of confidence about their post-cystectomy bodies. “Patients that have an external apparatus may be embarrassed and worry that their partner isn’t going to find them attractive,” Apolo said. Intimacy apparel for women with stomas is available and can make them feel sexier. But Apolo believes the most important way to feel comfortable after surgery is to talk openly to doctors, partners and other patients. There are communities on the internet, such as the Bladder Cancer Advocacy Network, where patients support one another and share information.

“It’s important that stories like this are written. I think the best way to empower people is with knowledge and resources because bladder cancer can feel very lonely after diagnosis,” Apolo said.

Finding a way back to pleasure

For most patients, the clitoris is unaffected by surgery and clitoral orgasms are still possible. However, even for those patients who lose clitoral sensitivity or those who struggle with vaginal intercouse, orgasm and pleasure are still achievable.

“Having this surgery doesn't mean the end of the sex life. There's a lot that women can do to continue a healthy sex life,” Apolo said. The most important part of that, she explained, is to communicate with your partner about what does and doesn’t feel good.

Bartos noted that sexual pleasure after a cystectomy may simply look different from before. “There’s still a great deal of pleasure to be had. If vaginal intercourse is uncomfortable, some patients will try anal intercourse or oral sex. It’s about what works for that woman. It just may not be what she’s always assumed sex to be like,” she said.

Bartos said that single women may have an easier time achieving pleasure after bladder cancer compared to those in committed relationships. “Single women progress through their new sexuality faster because they can pleasure themselves without pressure to satisfy someone else or feelings of self-esteem from a partner seeing them,” she wrote in an email.

Of course, a caring partner could be a great source of support, but Apolo finds that a woman’s personality plays more of a part than her relationship status. “It really depends on the person and how sexually active she was before the surgery,” she said.

Speaking up before treatment

One of the best ways to face bladder cancer and its impact is to be prepared. Women should speak openly to their urologists, oncologists and gynecologists about what to expect after surgery. “If you're kind of prepared that this is going to be a different way of life, you’ll be more ready for the outcome after treatment,” Apolo said.

Another important issue patients may want to discuss with their doctors is having children. Although most women diagnosed with bladder cancer are over 55, it is possible for women who are still of child-bearing age to develop the disease. Since treatment may involve removal of sex organs, younger women may want to discuss reproductive options, such as freezing their eggs, with their doctors before treatment begins.

People with bladder cancer should also ask their doctors about alternative treatment options, such as radiation and chemotherapy. Right now, the most accepted treatment for MIBC is aggressive surgery, but other options are under investigation and chemoradiation may be an option for certain patients. Doctors are also moving toward surgical methods that preserve sexual organs and nerves needed for sexual pleasure. According to Smith, the Johns Hopkins Women’s Bladder Cancer program has moved away from routinely removing pelvic organs during cystectomy and is advocating for procedures that leave organs and nerves in place, which might reduce sexual problems.

Sex may not look the same after treatment. Pleasure may come from a new place, and a woman’s body may feel different from before. But none of that means that she can’t enjoy sex after bladder cancer. She can find her way back to a full, satisfying sex life.

This resource was created with joint support from Astellas and Seagen.

- What Women Need to Know About Urothelial Bladder Cancer ... ›

- A Conversation With Dr. Sarah Psutka About Bladder Cancer ... ›

- Life After Diagnosis: Navigating the Things You Love with Urothelial Bladder Cancer - HealthyWomen ›

- Living with Bladder Cancer - HealthyWomen ›

- Mental Health and Urothelial Bladder Cancer - HealthyWomen ›

- How to Regain Intimacy When Your Partner Has Bladder Cancer - HealthyWomen ›

- Going Back to Work with Bladder Cancer - HealthyWomen ›