There are fashion shows. There are walks, runs, ceremonies, benefits, pink ribbons and special luncheons. There is a month devoted to remembering. And everything pink is sold with the promise of an eventual cure.

Are they beneficial to aid the person who is going through breast cancer? Well, yes, I suppose, or else they would not exist. For one thing, they raise very necessary funds. For another, they tell the world that we exist.

But on a much more personal level is something so fundamental to the human spirit; something that sounds so simple but is, in fact, much more complicated than the word implies.

It is much more personal. It is communication and support.

If you're reading this and you've been through, or are going through, a diagnosis of breast cancer, I think you understand what I'm trying to say. And if you are reading this and have not experienced the overwhelming feelings that come with a diagnosis of breast cancer, chances are you know someone who has. And you want to help, but maybe don't know how.

I don't think I'm speaking only for myself when I say that I needed—and at times, craved—understanding from the outside world. I wanted some reassurance that the other person understood, no matter how remotely, what I was faced with. And that need continues today, all these years later, because I know that I, for one, will never see the world in quite the same way as I did before my experience with breast cancer.

But the problem is that people are not always prepared to help. I used to think that many people had a hard time communicating with me because I was relatively young – 34 - when I was diagnosed. Because my friends, most of them in their 30s themselves, were not yet experienced enough with illness or hardship, I concluded that they couldn't possibly know what to say to me or do for me. And, thinking back, did they make blunders!

Like the woman I knew from our children's nursery school who made an obvious and abrupt about-face when she spotted me coming down the grocery aisle and again, weeks later, in the school parking lot. Or the cousin who phoned me a couple of days after I came home from the hospital and said, "I just went for my mammogram and thank goodness it was negative!" And how could I forget that call I got days after my surgery from another young mother who babbled on about what a shock it was to hear of my diagnosis because "We're all young—just like you..." Um, thanks for the reminder.

Sorry if I sound a bit peeved, but I was hurting. And what I now realize is that none of the hurt was intentional, but rather an attempt (however ill-fated) to say something— anything.

What I came to realize is that many people want to help but simply don't know how. That's why I reached out to dozens of breast cancer survivors to get their feedback on this crucial issue. While it's true that everyone is different—some women may want to talk while others prefer to keep to themselves—the common theme that came through was that just knowing someone out there cares is often comfort enough, and that sometimes the perfect words are none at all.

One survivor offered this: "As far as what people can do to help when someone is diagnosed, my answer is, anything! Don't turn away. Some family/friends don't know what to do or say. They rationalize that they don't want to intrude, so they back away."

A person who is going through breast cancer is emotionally raw and frightened. She needs support at this time. If you turn away, she is being hurt twice—once, from the diagnosis and then again from your (implied) rejection.

Don't know what to say? Even a simple, "I don't know what to say," is better than ignoring the person outright. It is not a rejection, but rather, an admission of caring.

Instead of allowing fear of saying or doing the wrong thing to make you do absolutely nothing at all, here's how you can help someone:

DON'T tell the person just diagnosed that you know a woman who just died, had a negative mammogram or recently had a scare. And don't tell her that you know just how she feels (unless you've also gone through a similar experience), because even though you may be the most empathetic person in the world, you can't possibly know.

DO admit that you might not know just what to say, but that you are here for her nonetheless. Let her know that you are willing to do anything she might need, even if it's just listening. (Another gesture that I'll never forget is what my former boss did for me the day I arrived home from the hospital. He traveled many miles through a bad snowstorm, pulled a chair up to my bedside, where I lay in a combination of shock and drug-induced haze, and sat, silently, for hours. No words were exchanged. In retrospect, no words could have helped as much as his quiet presence that day.)

DON'T label the person as though they are sick. Many women are so inundated with medical procedures, tests, etc., that they want to get back to "normal" as much as possible outside the doctor's office. One survivor told me, "I still see people who say, 'And HOW do YOU feel?' as if I'd just recovered from the plague! Many survivors don't want to be thought of as having permanent patient status…I even had a friend who introduced me to someone as, 'My friend who has cancer.' I'd had my surgery and was moving on."

DO remember to ask the person about her life, her children, her activities—anything that gives her joy outside of what she is going through. Invite her out to lunch, to a funny movie, for a day of shopping—anything that will take her away from the medical and put her back into everyday life.

DON'T shy away by ignoring the facts of the disease. It's frightening. Plain and simple.

DO acknowledge the person's fear. After all, it's real and appropriate. It's OK to say, "You must be scared." Talk about the cancer with her (if that's what she wants). If you've just read something pertaining to the subject, ask first if she'd like you to share the information with her. Follow her lead. You'll be able to tell in no time what she needs by simply listening.

DON'T drop out of sight or stay away.

DO be there—any way you can. Stay in touch. While a phone call is nice, if you're not sure if the person feels like talking, an email, text, note or a card is unobtrusive yet caring. Or, donate to a cancer research organization in honor of her. It's a touching reminder that you're thinking about her.

And finally, remember this. Everyone needs different things. Try to take your lead from them. Sometimes just being there, listening and being supportive are the greatest gifts you can offer.

If you would like more information about how to best help a person who has been diagnosed with breast cancer, here are some other sources:

American Cancer Society

https://www.cancer.org/treatment/caregivers/how-to-be-a-friend-to-someone-with-cancer.html

Breast Cancer Now

https://breastcancernow.org/information-support/facing-breast-cancer/how-support-someone-breast-cancer

Some helpful books:

"The Etiquette of Illness" by Sue Halpern

"Cancer Etiquette" by Rosanne Kalick

"Help Me Live" by Lori Hope

These, and other sources, include helpful information for caregivers, family and friends.

- How to Care for Someone Living With Breast Cancer ›

- Cooking for Someone Battling Breast Cancer: Quinoa Pasta Salad ›

- Overcoming the Fear of Breast Cancer - HealthyWomen ›

- Do You Know Someone Who Has Cancer? Here’s How You Can Help. - HealthyWomen ›

- Fighting Breast Cancer My Way - HealthyWomen ›

- El impacto del cáncer me inspiró para establecer la comunidad que necesitaba - HealthyWomen ›

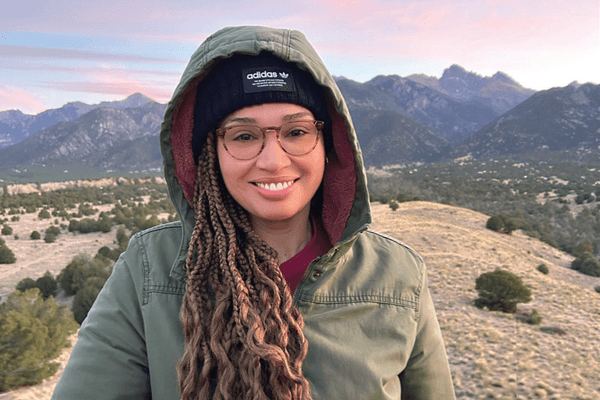

- A Cancer Shock Inspired Me to Create the Community I Needed - HealthyWomen ›