By Christopher Beem, Penn State

Decades ago I helped organize a conference that brought together vaccine skeptics and public health officials. The debate centered on what governments can and cannot demand from citizens, and what behaviors one can rightly expect from others.

It took place many years before the current coronavirus pandemic, but many things that happened at that conference remind me of our circumstances today. Not least, as a political theorist who also studies social ethics, it reminds me that arguments grounded in self-interest can often be correct – but still deeply inadequate.

The rationality of vaccine skepticism

I recall one participant summarizing her objection to vaccines in the following way: She said that the government demanded that she allow a live biological agent to be injected into her child's body even though it could not guarantee her child's safety. For these reasons, she claimed, she had every right to decide that her child would not receive the vaccine.

This woman's objection was driven by her suspicion that the MMR vaccine, for measles, mumps and rubella, caused autism. This claim has been shown, repeatedly and conclusively, to be without merit. Still, she was not entirely wrong. Many vaccines do contain live agents, though they are in a weakened or attenuated state. And while adverse and even serious reactions have been known to occur, such a risk is infinitesimally small. Indeed, the preponderance of evidence shows that the risk of harm or death to the unvaccinated child from infections such as MMR is far greater than any associated with receiving the vaccine.

But more importantly, this parent's decision to reject the vaccine affected more than just her child. Because so many parents refuse vaccination for their children, outbreaks of measles have taken place throughout the U.S. In fact, in 2019 the United States reported its highest number of cases of measles in 25 years.

COVID and vaccine hesitancy

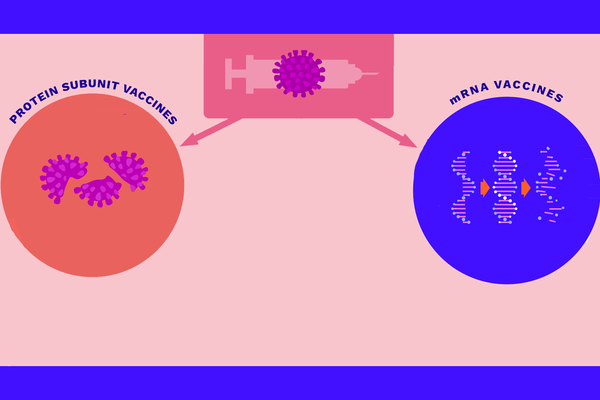

Many individuals are rejecting the COVID-19 vaccine for similar reasons – that is, reasons grounded in self-interest. They say that COVID vaccines are experimental, their long-term effects are unknown and that emergency authorization by the Food and Drug Administration was rushed.

In fact, while the vaccines were given emergency authorization to expedite their availability to the general public, they are not experimental but rather the result of years of already existing research on mRNA vaccines and coronaviruses – the family of viruses including SARS-CoV-2 that causes COVID-19. And they received authorization only after conclusive evidence showing they were indeed safe.

Those who reject the COVID vaccine also note that many receiving the vaccine have had an adverse reaction, including flu-like symptoms that are short-lived but often quite unpleasant. Cases of anaphylactic shock or blood clots have also happened, but they have been extremely rare, and safeguards on how to provide immediate care are in place for any such eventuality.

Here again the risks associated with the vaccine are extremely small, but for some people, still real. Therefore these individuals apparently decided that they would rather take their chances with the disease itself. Many are young and don't think the disease will affect them, and many more don't trust the doctors, scientists and politicians who they say are pushing them to take the vaccine.

One could readily dispute these claims, too. In fact, rising vaccination rates over the past few weeks show that many people have reevaluated the risks of remaining unvaccinated. Whether these people have seen evidence of the virulence of the delta variant or have seen for themselves that millions of people have taken the vaccine and are completely fine, their evaluation of their own self-interest has changed.

Nevertheless, many others remain adamant that these risks are unacceptable. Like that parent from many years ago, these individuals are not entirely wrong. There are risks associated with getting the vaccine. And knowing these risks, and knowing that they bear the costs of their decision, many Americans believe that they alone have the right to decide. What the government or anyone else wants is beside the point.

But here again, the costs of refusing the vaccine are not borne by the individual alone. Rising case numbers and hospitalizations, renewed restrictions regarding public events, even the emergence of the delta variant itself are happening largely because many millions of Americans chose not to get the vaccine. And for parents of children under 12 who cannot yet receive the vaccine – some of whom are immune compromised – the thought of returning to school this fall with infection rates again climbing no doubt fills them with dread.

Many would argue that this lack of concern for other people is immoral. The Golden Rule – do unto others as you would have others do unto you — manifests that concern for the well-being of others is at the core of morality. Those who choose not to take the vaccine ignore this concern and therefore act immorally. But, I would argue that their indifference to the welfare of others is not only immoral, it is also un-American.

Democracy and concern for others

Americans are a highly individualistic nation, and the spirit of “rugged individualism," or the idea of “pulling yourself up by your bootstraps," runs deep in American culture and history. In fact, from the nation's very beginning, Americans have accepted the notion that human beings care about themselves and those they love more than they do about other people.

At the time of America's founding, many contemporaries believed that a democracy is possible only if citizens love their country more than themselves. But America's founders rejected this idea. Human beings are not angels, James Madison said. The founders accepted the reality of human selfishness and developed institutions – especially the checks and balances among the three branches of government – whereby people's natural selfishness could be directed toward socially useful ends.

But neither Madison nor any of the other founders believed that human beings were merely selfish. Nor did they believe that a democracy could be sustained on selfishness alone. The Federalist Papers were written by James Madison, Alexander Hamilton and John Jay in support of the U.S. Constitution drafted in 1787. In Federalist 55, Madison presents this summation of human nature:

“As there is a degree of depravity in mankind which requires a certain degree of circumspection and distrust, so there are other qualities in human nature which justify a certain portion of esteem and confidence. Republican government presupposes the existence of these qualities in a higher degree than any other form."

Yes, Madison says, human beings are selfish, and one must not ignore that reality when one is deciding how to run a society. But people are not merely selfish. We are also capable of acting with honesty and integrity and of thinking for the good of the whole rather than merely ourselves.

More, Madison argued that this other side of human nature, this concern for others, had to be operative if democracy were to survive. In fact, he insisted that, more than any other form of government, a democracy depended on virtuous citizens. Speaking at the ratifying convention for the U.S. Constitution in his home state of Virginia, Madison said:

“Is there no virtue among us? If there be not, we are in a wretched situation. No theoretical checks – no forms of government can render us secure. To suppose that any form of government will secure liberty or happiness without any virtue in the people, is a chimerical idea."

Mere selfishness is ‘un-American’

Madison lived through the yellow fever epidemic of 1793. He even advised President George Washington about how he might address this health emergency. But there was no vaccine, nor even an understanding of what caused the epidemic.

While we don't know what Madison would have said about a vaccine, we do know what President Dwight D. Eisenhower said after the development of the polio vaccine. Eisenhower's words likewise affirm the idea that our democracy requires that we show concern for one another.

“We all hope that the dread disease of poliomyelitis can be eradicated from our society. With the combined efforts of all, the Salk vaccine will be made available for our children in a manner in keeping with our highest traditions of cooperative national action," he said.

Because of Madison and the other founders, the United States is a free and democratic society. Within very broad limits, Americans all have the right to make their own decisions. In some cases, Americans may even have the right to ignore the impact of their decision on others.

But a free society demands more of its citizens than mere selfishness. Political institutions can help direct and mitigate the effects of this natural human inclination to selfishness.

Throughout history, America's leaders have recognized that without concern for others, without the highest tradition of cooperative national action, democracy is in peril. People who decide not to get vaccinated must understand that their actions are not just selfish, they are un-American.

[Understand what's going on in Washington. Sign up for The Conversation's Politics Weekly.]![]()

Christopher Beem, Managing Director of the McCourtney Institute of Democracy, Co-host of Democracy Works Podcast, Penn State

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.