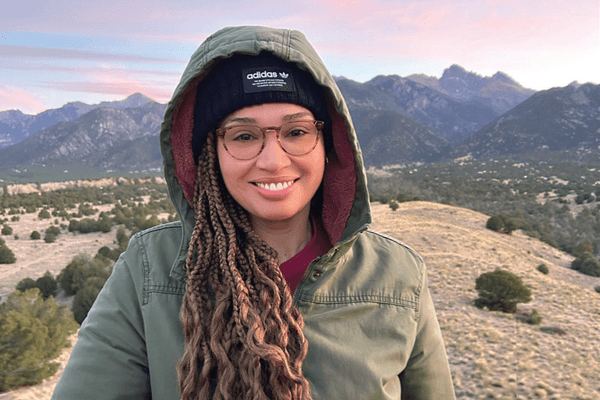

Twelve years ago, Maiya Hayes discovered a suspicious mass in her breast during a self-exam. She quickly made an appointment with her gynecologist, who helped schedule the tests that revealed she had stage 3 breast cancer.

Her oncologist told her that the aggressive nature of her breast cancer, which had spread to the lymph nodes under her right armpit, meant a 60% chance of recurrence. The diagnosis came as a shock to Hayes, who had just turned 30 earlier that year.

"At first, I was very naive about the whole thing — probably because I had the 'I'm immortal' mindset that comes with being younger," Hayes said. "I was scared and devastated and honestly thought I wouldn't live to see age 40."

As a Black woman, Hayes was more likely to develop breast cancer under the age of 45 than women in any other racial or ethnic group. And while, aside from skin cancer, breast cancer is the most prevalent form of cancer for women of all ethnic groups in the United States, Black women under age 50 are 40% more likely to die from it than white women and twice as likely to die over age 50.

The higher death rate is even more jarring considering that Black women are less likely to develop breast cancer between the ages of 60 and 84 than white women.

"This difference is unacceptable and we're working to figure it out," said Dr. William Cance, a surgical oncologist and chief medical and scientific officer for the American Cancer Society. "It's complicated — clearly disparities such as access to high quality care and treatment play a role, but there are also biological differences that we don't fully understand."

For example, Black women are also more likely to be diagnosed with invasive cancers or triple-negative breast cancer, which are more difficult to treat and decrease the likelihood of longer-term survival.

Addressing the disparities

Helaine Bader, HealthyWomen's senior advisor on health education, said Black women are often diagnosed later than white women, leading to a delay in treatment. Early detection and treatment make a significant difference in survival outcomes, especially for the invasive forms of breast cancer Black women have a higher risk of developing.

Even after a diagnosis, Black women were more likely than white women to experience delays in care. A recent study found that Black women had the start of their treatment delayed by two months or more after diagnosis and had a longer period of care. Race was more strongly connected to this delay than socioeconomic status.

"We know many underserved communities experience these disparities in care, and breast cancer is no exception," Bader said.

Cance mentioned a scenario he encountered often in his outreach efforts: Women would receive a mammogram but have the results sent directly to their homes with no direction about following up with a medical provider. Lack of funds to pay for treatment, limited access to health care facilities and even fear could prevent women from seeking treatment after screening, and the COVID-19 pandemic has only exacerbated these challenges.

Seeking help

There are steps Black women can take to reduce their breast cancer risk or improve their chances for survival if they are diagnosed. Self-examinations, mammography over the age of 40 and immediate treatment following a diagnosis are a must; younger women outside the typical screening age should consider their family history of breast cancer to determine whether they're in a high-risk group. Cance suggests talking to a doctor about genetic testing and discussing the potential need for early screening and medication regimens to reduce risk.

Research is taking place to detect cancer risk through blood tests that can help reduce the biological disparities between racial and ethnic groups.

Eating well, exercising and losing weight also help decrease breast cancer risk and improve treatment outcomes. Research shows that women who are obese have decreased survival rates from breast cancer even with timely treatment and can experience more complications related to their treatment.

A second chance

Hayes had many factors working in her favor as she started her treatment, including early diagnosis and good health insurance through her employer. Her care consisted of a lumpectomy in her right breast, an axillary dissection of the lymph nodes in her right armpit, 16 rounds of chemotherapy, 35 rounds of radiation and a year's worth of infusions of a drug to inhibit the development of cancer cells. She also took a drug to block estrogen receptors — as naturally occurring estrogen can increase breast cancer cell growth — for 10 years.

Hayes said she knew she'd lose her hair and feel sick, but she was shocked at how debilitating her nausea, vomiting and fatigue became.

"During the lowest moments of my chemo treatments, I felt so bad that I cried to God — and at that point, I wasn't a very spiritual person," she said.

In the years following her treatment, Hayes has worked to keep her immune system healthy by eating well and exercising, and she maintains her mental health through psychotherapy. She never misses a routine checkup or screening and quickly sees a doctor when she's sick. She's also taking extra precautions by limiting interactions outside her home during the pandemic.

During her journey, Hayes became a member of Gilda's Club Metro Detroit, a local branch of the national support group for cancer survivors, their friends and families. She's met new friends and mourned the loss of others, including women in her age range who died from breast cancer.

"After finishing my chemo and radiation treatments, I realized that my life would never go back to what it was pre-cancer," said Hayes, who turned 42 in April. "I decided to stop stressing about trivial things and start being more open-minded. I realized how fragile life is and how fortunate I am to be alive."

Resources:

American Cancer Society

Breastcancer.org