Medically reviewed by Maureen Farrell, M.D.

This resource was originally created for HealthyWomen's military health program, Ready, Healthy & Able.

The Female Reproductive System

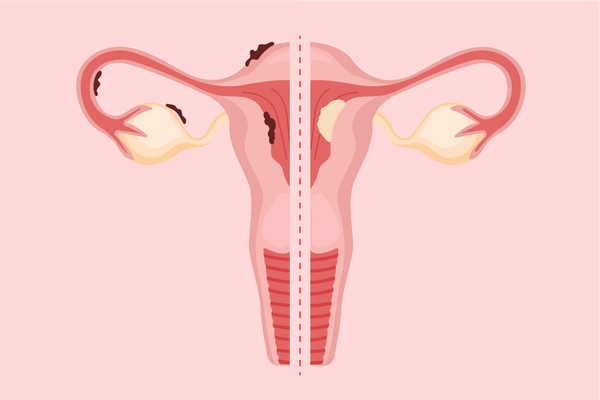

- Uterus

- Ovaries

- Fallopian tubes

- Cervix

- Vulva

- Mons

- Labia majora

- Labia minora

- Clitoris

- Urethra

- Vaginal opening

Menstruation (The Period)

Typically begins in females between ages 11 and 16

The average cycle is around 28 days but can range from 21 to 35 days

The cycle starts on the first day of the period and ends on the first day of the next period

The menstrual cycle occurs in three stages

o Follicular phase (1st day of period until ovulation)

- Days 1 to 5

- The uterine lining breaks down and is passed out of your body through bleeding (menstruation)

- Days 6 to 10

- Estrogen rises and the lining of the uterus thickens

- Follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) causes follicles (small cysts) to grow and eggs to grow inside those follicles

- Follicles release more estrogen, helping the lining of the uterus get thicker and prepare for a fertilized egg

- Days 10 to 14

- One follicle will form a mature egg

o Ovulatory phase ( days 14 to 16)

- A spike in estrogen causes an increase in luteinizing hormone (LH)

- This rise triggers a follicle to pop open and release an egg which is swept up by one of the fallopian tubes. This is called ovulation.

- If unprotected sex occurs, the egg may be fertilized when a sperm and egg combine

- If the egg is not fertilized, it will dissolve in the next few days

o Luteal phase (days 15 to 28)

- The follicle that held the egg becomes the corpus luteum, which makes the hormone progesterone

- Progesterone keeps the lining of the uterus healthy and supports the growth of a pregnancy

- The egg moves from the fallopian tube to the uterus

- If the egg is fertilized and implants into the uterus, the person will become pregnant

- If the egg passes through the uterus, the corpus luteum stops producing progesterone, which causes the lining of the uterus to break down and shed during the period — and the cycle starts all over again

Pregnancy

- The first day of pregnancy is dated from the 1st day of your last period before the pregnancy

- A full-term pregnancy is 40 weeks (280 days) and is broken into 3 trimesters o 1st trimester: implantation to week 12 o 2nd trimester: weeks 13 to 28 o 3rd trimester: weeks 29 to 40

Postnatal

- The 12 weeks following delivery are the 4th trimester.

- Breast milk starts to come in several days after delivery.

- Lochia, a period-like discharge that contains blood, mucus and uterine tissue, lasts for several weeks.

- The uterus will shrink from around 2.5 pounds (the size of a watermelon) immediately post-birth to around 2 ounces (the size of a lemon) in about 6 weeks.

- Estrogen levels drop and can lead to the baby blues or postpartum depression, which is more severe and lasts longer. Postpartum depression affects up to 1 out of 5 women after delivery.

Menopause

- A natural process that typically occurs between ages 45 and 55 , marking the end of a woman’s menstrual cycle and the end of the ovaries releasing eggs

- A woman is said to be in menopause when she has gone 12 months without a period.

- Begins with perimenopause, the transitional period before menopause where estrogen levels begin to decrease. Perimenopause often begins in the mid-40s but can begin for some women in their 30s.

Talk to your healthcare provider if you have questions about your reproductive cycle or need help managing symptoms.