As told to Nicole Audrey Spector

Throughout my college years, every visit home for Christmas brought an increasingly alarming discovery: My grandmother was shrinking. I mean, really shrinking.

We didn't know she had osteoporosis. We just thought, "Grandma is getting old. She's in her late 70s. Shrinking happens with age."

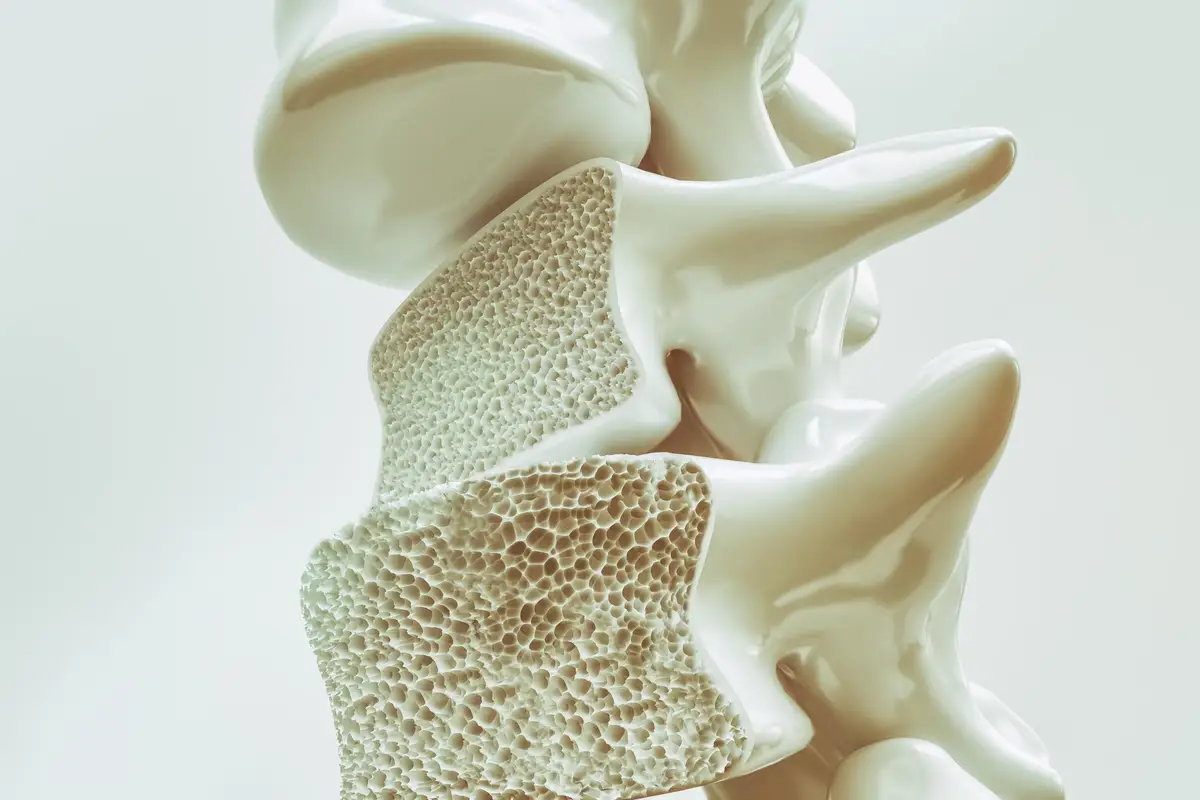

After menopause, women lose bone density, which increases risk for developing osteoporosis, a disease in which new bone creation doesn't keep pace with bone loss, so the remaining bone tissue becomes brittle, leading to that familiar hunched posture, back pain (caused by spine fractures or collapsed vertebra), an increased risk for bone breaks, height loss, and potential loss of mobility.

During those college visits home to grandma, I was pursuing my lifelong dream of becoming a clinician who specialized in orthopedic surgery. Though I was obsessed with bones from an early age, studying bone diseases like osteoporosis wasn't high up on my list of things to do. I wanted to dedicate myself to fixing bones rather than to preventing their decline.

But I started to notice how scarcely informed my grandmother and the rest of the women in my family were about osteoporosis. They were familiar with the disease, but they didn't know that approximately 10 million Americans have osteoporosis — 80% of them women. Nor did they know that a woman's risk of breaking a hip because of osteoporosis is as likely as her risk of breast, uterine and ovarian cancer combined.

The media didn't help any. All of the awareness campaigns around osteoporosis centered on older non-Hispanic white women, and occasionally Asian women. As Black women, we never saw anyone who looked like us as a face of the disease. So, when I asked my grandmother (then in her mid-70s) if she'd had a bone density test — which all women should get at the age of 65 or younger if you have certain risk factors for bone loss — it was no surprise that she had no idea if she'd had one.

By the time I was in grad school, I knew I needed to shine a light on the risks, outcomes and management of osteoporosis, particularly as it affects people of color and, more narrowly, the Black community.

This meant veering my focus away from becoming a physician and instead becoming an epidemiologist, someone who studies how often diseases occur and why. I went on to achieve my goal and am now an associate professor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham with a research focus on osteoporosis epidemiology.

My time is spent researching prevalence, risk factors and outcomes of osteoporosis to help prevention in women. Much of my work is devoted to enhancing education and awareness around osteoporosis in the Black community, which has been historically underserved.

Some studies suggest that Black women are at lower risk for osteoporosis than non-Hispanic white women, but we must challenge the integrity of these findings by taking a step back and asking: Are we looking at Black women as widely and as closely as we are at other populations?

In many osteoporosis studies, which are often sorely outdated, Black women are less represented than non-Hispanic white women. We also know that Black women are not getting screened for osteoporosis as often as their counterparts of other races and ethnicities, so they are getting treated less often.

Why is this the case? Are Black patients not asking for bone density tests or are doctors not ordering them?

We are still investigating, but it could be a little bit of both. Black patients aren't asking for bone density scans because they either don't know they should be asking for them, or providers aren't rising to the occasion because of unconscious bias and misconceptions about bone health in the Black community.

Whatever the reasons for underscreening for osteoporosis in Black women ages 65 and over, it's a problem that needs urgent attention. If you're not screened for osteoporosis, you cannot be diagnosed, and thus you cannot be treated. This naturally leads to poor outcomes and partly explains why Black women have a 25% higher mortality rate tied to bone fractures than non-Hispanic white women.

Would there be a racial disparity in outcomes if access to screening and treatment were the same?

Today, I am devoted to increasing proactive behaviors on the patient's part as well as highlighting how Black women are underserved in scientific literature so I can inspire change on the provider end, too.

Not only do I fiercely advocate for bone density scans at the age of 65, I also encourage people of all ages and races to pay attention to the importance that nutrition and exercise play in overall bone health. You need to eat whole foods that are high in protein, calcium and vitamin D. You also need to do weight-bearing and strength-building activities. Talk to your doctor about any health conditions that may increase your risk for bone loss and/or fractures such as rheumatoid arthritis or diabetes — and the list goes on.

I can gladly say that everyone in my family is now up to date on their bone health (thanks largely to me, who is basically a walking tutorial everytime we get together). But we need bigger systemic change.

The medical field has at least recognized that there are differences in osteoporosis management by race and ethnicity, and there is a desire to get at the root cause of these differences. Now we just need to figure out how we take the information we've gained and move it forward.

Some of it will take politics and some of it can be achieved by grassroot movements. But much of it will also take people like me, who are compiling and advancing research on osteoporosis to help fuel the fight against it. I'm also here to remind everyone that if you want to stay out of a nursing home and be there for your grandkids, you need to take care of your skeleton.

And please, get that bone density scan as soon as you're eligible.

This resource was created with support from Amgen.

- How is Osteoporosis Diagnosed - HealthyWomen ›

- Osteoporosis: Knowing – and Owning – Your Numbers ... ›

- Osteoporosis - HealthyWomen ›

- How to Prevent Osteoporosis - HealthyWomen ›

- For Women, Osteoporosis Leaves Physical and Emotional Scars - HealthyWomen ›