By Neelum T. Aggarwal, MD

Rush Alzheimer's Disease Center

SWHR Interdisciplinary Network on Alzheimer's Disease Member

An estimated 5.2 million Americans live with Alzheimer's disease (AD). Of these Americans, 5 million are over the age of 65 years old. AD is the third leading cause of death in older adults and is the only top 10 cause of death in the United States with no disease-modifying treatment or proven treatment for prevention.

Even with the statistics mentioned above, it is surprising that the diagnosing of the disease remains problematic. In many routine health care visits, clinicians fail to ask, "Are there changes in thinking or memory?" And many cases of dementia go undiagnosed or unclassified.

This troubling trend, coupled with the staggering number of projected cases of dementia in the coming years, led the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer's Association (NIA-AA) to partner and propose that a critical review of the existing research be conducted with the goal of recommending updated diagnostic criteria and guidelines for AD.

In 2011, a series of articles was released from the NIA-AA Working Group. The resulting new diagnostic criteria incorporated two important changes:

- Discussion of the early stages of AD, as well as the introduction of the terminology "presymptomatic Alzheimer's disease"

- The importance of biomarker tests to aid in the diagnosis of AD

Out With the Old (Guidelines) and in With the New

Previous guidelines for diagnosing dementia and AD relied heavily on the clinical judgment of a health care provider (HCP) about the cause of a person's symptoms based on reports from the individual, spouse, family member or friend, in addition to "data" obtained from the clinical evaluation (cognitive tests, a neurological exam, a brain scan and blood tests).

Often, however, the dementia diagnosis presented a clinical diagnostic challenge because clinical signs and symptoms, particularly early on, could be consistent with more than one cognitive syndrome. This challenge, coupled with variability in clinical knowledge and experience by the HCP in diagnosing and treating patients with dementia and nonconclusive clinical tests that could signal a dementia, only added to the confusion surrounding the diagnosis and subsequent care for patients with cognitive disorders.

Alzheimer's Disease in Three Stages

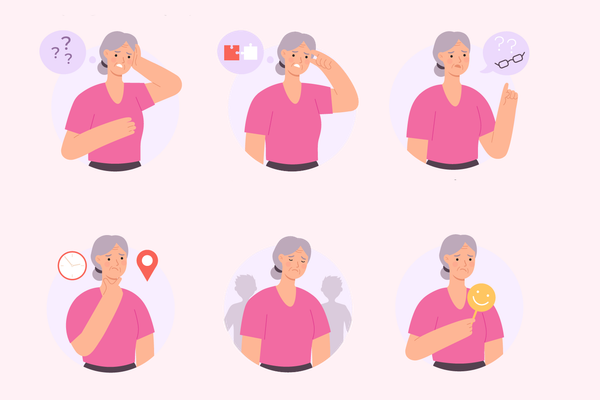

Enter the new criteria for AD that proposed three distinct stages: preclinical Alzheimer's disease, mild cognitive impairment (MCI) due to Alzheimer's disease, and dementia due to Alzheimer's disease.

The importance of this multistep staging system cannot be overstressed. It was the first time that a staging system for AD attempted to combine clinical symptoms with evidence of brain changes (via biomarkers). The proposed staging resulted from the mounting evidence of biomarker data that suggested AD begins before the development of clinical symptoms and that emerging technology could identify brain changes that precede the development of symptoms.

So, What Exactly Does Each Stage Mean?

Persons with preclinical Alzheimer's disease have measurable changes in the brain, cerebrospinal fluid, and/or blood biomarkers that may indicate the earliest signs of the disease, but they have not yet developed symptoms such as memory loss. This preclinical or presymptomatic stage reflects our current thinking that AD-related brain changes can occur 20 years before symptoms occur.

Although the criteria for this "preclinical stage" of AD are in place, it is not routinely being used by HCPs. More research in the area of biomarkers and their prognostic value as tests to predict the development of dementia needs to be done before HCPs begin to universally use this term and render a diagnosis of preclinical Alzheimer's disease in their patients.

In contrast, MCI due to Alzheimer's disease has gained more recognition among the medical community, and HCPs are increasingly using the terminology. Individuals with MCI have mild but measurable changes in thinking abilities that are noticeable to the affected individual, work colleagues or friends, but these symptoms are not severe enough to impact the individual's ability to carry out everyday activities.

Dementia due to Alzheimer's disease is the third stage in the disease classification. In this stage, people typically have memory, behavioral and other thinking changes that are severe enough to impair their ability to function in daily life and that are thought to be due to AD brain changes.

There is still more to be done in investigating new AD risk factors, discerning how biomarkers may assist in establishing the risk of dementia, establishing how risk factors vary by gender, and translating these findings to clinical practice. The Society for Women's Health Research's Interdisciplinary Network on Alzheimer's Disease is committed to advocating for these goals to inform prevention and provide guidance for research, clinical trials and policy. Click here to learn more about SWHR's work in Alzheimer's disease.