MONDAY, Nov. 5, 2018 (HealthDay News) -- Some bystanders may avoid performing CPR on women because they fear hurting them, or even being accused of sexual assault, preliminary research suggests.

In two new studies, researchers tried to dig deeper into a puzzling pattern that has been seen in past research: Women are less likely than men to receive bystander CPR if they go into cardiac arrest in a public place.

One study confirmed that real-world phenomenon in a controlled setting: It found that even in "virtual reality" simulations, participants were less likely to perform CPR when the virtual victim was female, versus male.

People performed CPR on 65 percent of male victims, but only 54 percent of females.

A separate study, which surveyed 54 adults, turned up some possible explanations.

Respondents said bystanders may worry about hurting a woman while doing CPR chest compressions -- or fear being accused of sexual assault. Some said people also might believe women's breasts get in the way of CPR.

The respondents also cited a long-standing misconception: Women are less likely to have heart problems than men.

But the reality is that heart disease is the leading killer of U.S. women and men alike, according to government figures.

And when cardiac arrest strikes, CPR can be lifesaving, regardless of sex, said Dr. Sarah Perman, who led the survey.

People in cardiac arrest need immediate chest compressions, said Perman, an assistant professor at the University of Colorado School of Medicine in Denver.

"Providing this lifesaving procedure for women should be normalized, and not sexualized," she said.

In the United States, more than 356,000 people suffer cardiac arrest outside a hospital each year. Only about 11 percent survive, according to the American Heart Association (AHA).

Survival is dismal because without emergency treatment, cardiac arrest is fatal within minutes. But quick CPR can double or triple survival odds, the AHA says.

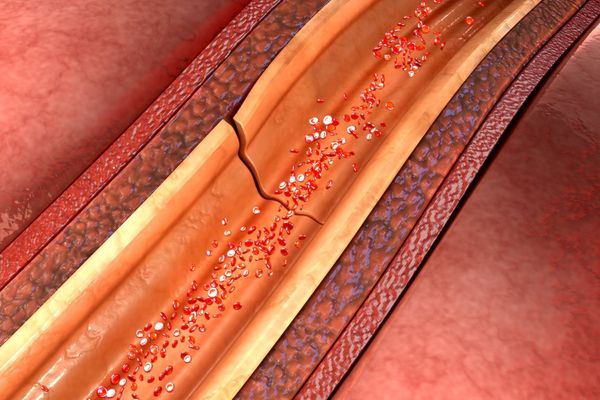

Cardiac arrest occurs when the heart suddenly stops beating and cannot pump blood and oxygen to the body. If a bystander performs CPR, that keeps the victim's blood circulating, buying time until paramedics arrive. Cardiac arrest is not a heart attack, which is caused by an artery blockage that diminishes blood flow to the heart.

"There is still a lot of misunderstanding about cardiac arrest and CPR," said Dr. Aaron Donoghue of the AHA and the University of Pennsylvania.

Men and women benefit equally from CPR chest compressions, Donoghue said, adding that the notion that it could injure women is "false."

As for fears of being accused of sexual assault, Donoghue noted that chest compressions are performed on the breastbone (also called the sternum, it's the long flat bone in the center of the chest) -- not the breasts.

"It would be terrible for that fear to deter a would-be rescuer from performing CPR," said Donoghue, who was not involved in the new studies.

"Doing nothing is always worse than doing something," he added.

For its pilot study, Perman's team surveyed 54 U.S. adults. Participants were asked: "Do you have any ideas on why women may be less likely to receive CPR than men when they collapse in public?"

Their answers reflect their personal perceptions, Donoghue pointed out. So, he said, it's hard to know whether witnesses to cardiac arrest really do act on such beliefs in the real world.

Perman agreed, saying more research is needed to understand why women are less likely to receive CPR. She and her colleagues have already conducted a larger survey, she said, but the results have not been published yet.

For now, Donoghue suggested people educate themselves about cardiac arrest and CPR. The AHA website is one place to start, he said.

Both studies are scheduled for presentation Nov. 10 at an AHA meeting, in Chicago. Research presented at meetings is typically considered preliminary until published in a peer-reviewed journal.

SOURCES: Sarah Perman, M.D., assistant professor, emergency medicine, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Denver; Aaron Donoghue, M.D., volunteer expert, American Heart Association, and assistant professor, clinical anesthesiology and critical care, University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, Philadelphia; American Heart Association Resuscitation Science Symposium, Chicago, Nov. 10, 2018

Copyright © 2018 HealthDay. All rights reserved.