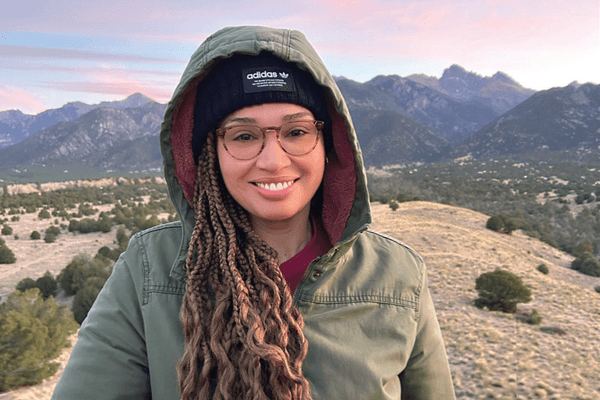

The most common question I got after I told people about my breast cancer diagnosis was this: "Does breast cancer run in your family?"

And before I knew better, I probably would have asked this question, too.

The answer: no, it didn't. No one in my family had had the disease—until me, of course.

But the fact is that only 2 percent (this small number surprised me, too!) of breast cancers in U.S. adult women occur due to inherited factors. Most inherited cases of breast cancer have been associated with two genes—BRCA1 and BRCA2. These two genes help breast cells grow normally; when there is a defect or abnormality in the genes, there is an increased risk of breast cancer. Women with this gene abnormality have a 50 percent to 85 percent risk of breast cancer by the age of 70, as well as an increased lifetime risk for ovarian cancer.

Although you may have a relative with breast cancer, most of these cancers are not caused by a defect in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene. It's important to note that these abnormalities account for just about 10 percent of breast cancers. And, if one family member has this abnormal breast cancer gene, it doesn't mean that all family members will have it, either.

Confusing, yes.

Searching for an explanation as to why I developed breast cancer at a relatively young age, I met with a genetic counselor from Yale University once I had completed my chemo treatments. I should mention that I am of Ashkenazi Jewish heritage. This group, Eastern European in origin, has been found to be more likely to have mutations in these genes than the general population.

The visit consisted of three sessions. The first session was an informal meet-and-greet where I discussed my own medical history with the counselor and told her, in depth, about my diagnosis and treatment and why I wanted to be checked for the gene defect. She sent me home with a comprehensive health questionnaire to bring to my second visit. I brought my mother along on that visit, where we discussed—really, retraced—my family's health history, building a tree, branch by branch. It is best to trace back at least three generations and to know the type of cancer each relative has had and their age at diagnosis. I thought perhaps my mother would know more about her grandparents and great-grandparents than I would. But that can be tricky. Aside from remembering back that far, a lot of people died of "unknown causes" that could have been an undiagnosed cancer. Then, the counselor took a cotton swab and rubbed the inside of my cheek (today the test is done by drawing blood). That was it.

A couple of weeks later, I drove back to my last and final meeting to discuss the findings. (There are, not surprisingly, huge psychological and emotional implications of genetic testing; hence, my anxiety.) I had such trepidation I could barely stay within the lanes on the highway. My mind raced with thoughts of a positive finding: Would I go ahead and remove my ovaries to minimize my increased risk of ovarian cancer? (I think it's important to know this fact: the American Cancer Society says that women with a BRCA mutation, by removing their ovaries—which are a main source of estrogen in the body— may reduce their risk of breast cancer by 50 percent or more.) Would I have my children tested, too (even though they were boys)? Would my sister, my mother, my nieces, all need to be tested, too?

Turns out I did not have to address any of these scenarios: My test was negative for any defects in these genes. My breast cancer fell into the "unknown" category of causes. Not that I still didn't wonder about why it happened in the first place…and I still wonder today, all these years later. But it was one of those things for which I'd never have a concrete answer.

You might want to get tested to see if you are at a higher risk of developing breast cancer. How do you know if you're more likely to have this abnormal breast cancer gene? Here are some helpful guidelines to help decide if you should be tested.

- Blood relatives (grandmothers, mother, sisters, aunts) on either your mother's or father's side of the family who have had breast cancer diagnosed before age 50.

- Both breast and ovarian cancer runs in your family, particularly in one individual.

- Women in your family have had cancer occur in both breasts.

- You are of Ashkenazi Jewish heritage.

- You are of African American heritage and have been diagnosed with breast cancer at 35 years or younger.

- A man in your family has had breast cancer.

But keep in mind that testing can be confusing. Sometimes it is inconclusive. And a positive result doesn't indicate you'll definitely get breast cancer. Instead, it means you are at high risk of developing breast cancer. That might lead you to be extra-vigilant with your mammograms and other screening methods. You might want to discuss other preventive measures with your health care team, like chemoprevention.

Some women opt for prophylactic mastectomies and/or removal of their ovaries because they feel especially vulnerable and nervous.

It's best to sit down with your doctor and discuss your concerns before you schedule the costly testing (it could run up to about $3,000 and is not covered by all health insurance). If you do test positive for the genetic defect, you will want to know, ahead of time, what your options will be.

If you want to read more, here is an excellent overview of issue from the National Cancer Institute: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/genetics/genetic-testing-fact-sheet. There's also a Web site, www.facingourrisk.org (FORCE), that contains information about genetic testing as well as risk management.

Like anything else, there are no black and white absolutes—there are pros and cons. (Sometimes, I guess, gray is a color we just have to learn to live with.)

My opinion? The right choice is what makes you feel most comfortable going forward. And remember—many factors can affect your risk for breast cancer, not just genetics. Although there are many you cannot control—like genetics, age and race—there are many you can control, including what you eat, how much you exercise and whether you smoke.