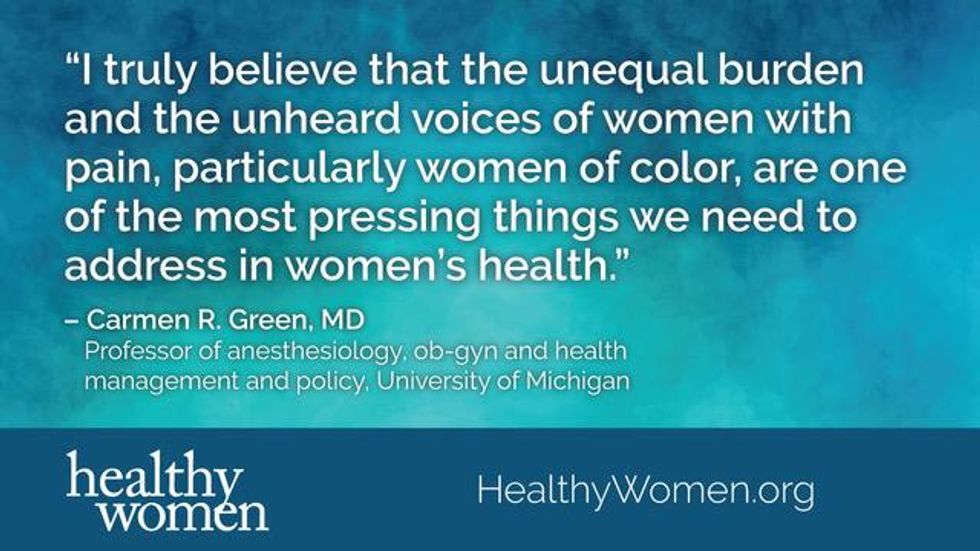

Carmen R. Green, MD, professor of anesthesiology, obstetrics and gynecology, and health management and policy, at the University of Michigan answers HealthyWomen's questions about the impact of bias on access to care for women with chronic pain conditions.

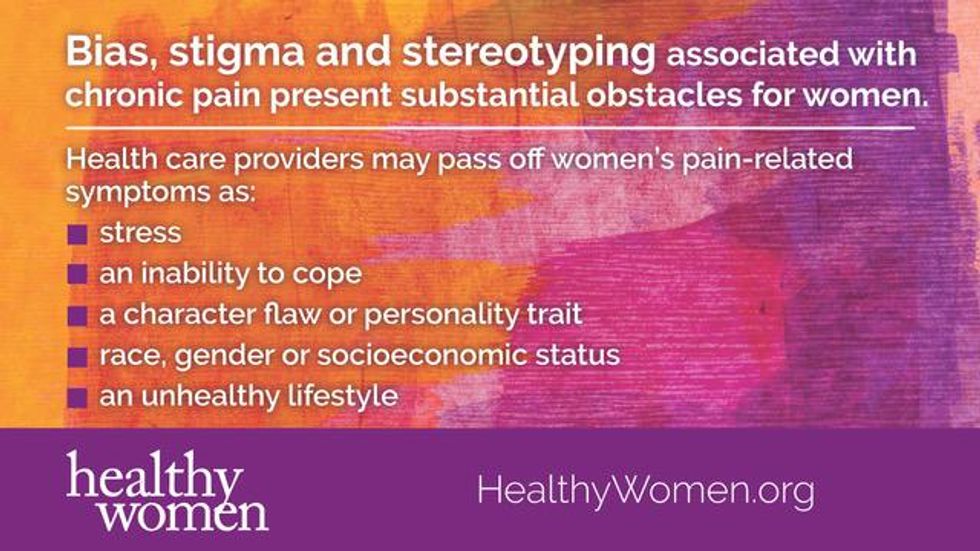

Women living with chronic pain face many challenges and disparities when it comes to diagnosis and treatment. Bias often is one of the least acknowledged obstacles. But bias—on the part of medical providers and the health care system—if not checked, alters the positive therapeutic relationship a patient should expect, and often affects its outcome.

What is bias?

Bias affects how we view the world and how we perceive others. Biases can be negative—believing that overweight people are lazy—or biases can be positive—believing that tall people are smarter.

Sometimes we're aware of our personal biases—an aversion, perhaps, to dogs; sometimes our biases are unconscious—that is, we aren't aware of them. Yet, everyone has biases, including health care professionals.

Bias is, as you might expect, about race; but also sexual orientation, gender, weight, age, socioeconomic status, disability and even height. A bias can be protective. If you once were bitten by a dog, your bias against dogs could be reasonable. Regardless of their cause, however, bias can get in our way. In health care delivery settings, bias may prevent us from making certain that all people get high-quality care. It interferes with access to appropriate care and can result in poorer health outcomes.

Stereotyping and stigmatizing are types of bias. When you look at somebody and think, "Because I see this, I must assume that." The perception that all inner-city chronic pain patients are black and are drug-seeking, or worse yet, are diverting their pain medications, is one example of a harmful stereotype that affects appropriate care delivery. An example of a stigmatizing condition is thinking all women with HIV have abused drugs. This is not the case in either example.

How does bias play into the treatment of chronic pain in women?

What we know is that women—and particularly women of color—are less likely than men to have their pain assessed and treated appropriately. Women are at risk for suboptimal pain assessment and treatment and also are less likely than men to receive pain medication when they have chronic pain; women are more likely to receive sedatives. We even find that women, particularly minority women, are at greater risk of having their chest pain discounted. In addition, it often takes women multiple visits with health care providers before they receive a diagnosis or referral.

Bias is definitely worse—and more damaging—when it comes to people of color. For instance, we found that pharmacies in primarily white neighborhoods carried a sufficient supply of opioids, even in low-income communities, while those in minority neighborhoods, even in higher-income neighborhoods, had sufficient supply only half the time. This showed us that race is protective if you are white, but money is not protective if you are a person of color.

So, even if you get a prescription for your chronic pain, that pharmacy may choose not to have it. Systemic variability, like these examples of institutional barriers, are more common for black women patients.

How does this play out when it comes to pain?

Research shows that health care providers' attitudes toward women, minorities and pain itself, especially the cause of pain, play a role in how those with chronic pain are assessed and treated. For instance, nonwhite patients are less likely to have their pain adequately treated than white patients. In one study, primary care physicians received a clinical vignette of a chronic pain patient who was either white or black and either had a "challenging" or "non-challenging" communication style, and confident, dejected or angry nonverbal behavior. All exhibited the same symptoms and level of pain. How the patient looked and behaved played a significant role in whether they received pain medication.

This is not unique; numerous studies find racial and gender differences when it comes to prescription pain medication, with clinicians holding the mistaken belief that minority patients are more likely to abuse prescription pain medications than are white patients. However, there is no data to suggest that racial and ethnic minorities are more at risk or more likely than are whites to abuse prescription pain medication.

Even how we diagnose problems differs in these populations. Unfortunately, we have tended to "medicalize" addiction for Caucasians and "criminalize" addiction for people of color. The question arises as to whether there has been overprescribing for some populations and appropriate or under-prescribing for other populations. The reality is that there is no data to suggest that people of color are more likely to misuse or become addicted to opioids than Caucasians.

Bias should not affect interactions between health care providers and patients, but it can and does. And, it is a two-way street. I believe patients want me to be objective, fair and competent in how I assess their pain and make treatment recommendations. I hope they expect high-quality care. Yet, I know that their previous experiences with the health care system and providers may change their expectations, leading to poor trust and lower expectations regarding the care they received or will receive. They, too, may have biases about me based upon my race, gender or even that I am a physician, so stereotyping can be a two-way street. We are all human beings, and we have all fallen short. With that being said, social, economic and behavioral health determinants impact women living with pain across their life course.

Bias may be at play if you have the sense that your health care provider isn't taking your pain complaints seriously—perhaps by not acknowledging your pain or by not providing adequate treatment. The ultimate goal is for the patient and their physician to be health care partners. This requires patients to participate in their care—by educating themselves and asking questions, and by doctors listening and asking clarifying questions.

How do I deal with a health care provider's bias or other issue that affects my care?

Here's where communication is crucial. First, stay calm and stay objective. Second, ask questions and be as specific as you can in describing your pain. For example, subjective terms such as, "It hurts," are less helpful. Instead, use objective terms such as, "The sharp pain goes down my leg and keeps me from walking my dog." Third, ask questions to get the health care provider to explore his or her own internal feelings. For instance, "Why do you think I don't need a pain reliever?" "What would you recommend if your sister or daughter were sitting here with this problem?" Lastly, I always recommend having an advocate.

But, in the end, if you feel that your health care provider isn't listening to you and minimizes your pain experience or doesn't treat you with respect, then it may be time to find a new provider. Check with your friends and neighbors for recommendations. You can also contact your local medical society for information. Patients get to choose who is on their health care team. If finding a new provider is an obstacle for you, a patient advocate can help you navigate the interaction with your current provider.

Pain is like a thief in the night who steals our physical, mental and social health and well-being. No one should have to live with pain when we have treatments available, including physical therapy, counseling, medications, nerve blocks and other therapies.

With that being said, I truly believe that the unequal burden and the unheard voices of women with pain, particularly women of color, are among the most pressing things we need to address in women's health.

This resource was created with support from Pfizer.